With depth and detail, Vaclav Smil tells us how we got here. The machines, the processes, and the energy sources. With this wealth of knowledge, he refuses to make grand predictions. What about the rest of us? What are we to do with this information?

At Energy Disruptors this past fall, Bruno Maçães was in Calgary, giving attendees a masterclass in world affairs. He is writing a new book featuring fresh ideas on the geopolitics of technology, money, and energy and is using his Substack newsletter as a platform for some of his research. In his latest post, he asks new questions about how to think about Smil’s work.

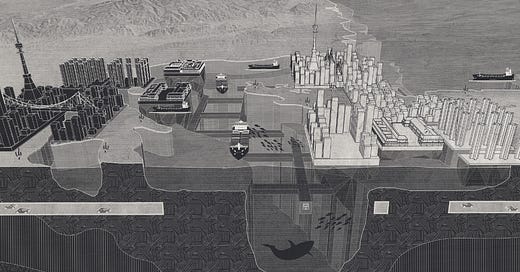

In the transformations of modern society we already witness a world illuminated and powered by electricity, even before that extends to ontological reality. And in urbanisation we can detect the flight from nature towards a virtual existence of office cubicles, and supermarkets, where the wilderness is reduced to a holiday experience.

Modern civilization is built upon a suite of innovations developed prior to World War One. Food, shelter, communications, mobility, and production were all revolutionized, harnessed by the energy density and attributes of fossil fuels. A human transported from 1823 to 1923 would find a vast array of unrecognizable environments and behaviours. A human transported from 1923 to 2023 would find a suite of improvements and optimizations. Without consciously knowing it, humans were already building artificial worlds early in the 20th century, capable of protecting civilization from nature's dangers and inhospitable volatility. Clean water, abundant calories and 22-degree environments are now the norm rather than the exception.

Taken in isolation, stocks of oil and natural gas could last for a few more centuries, but that is the wrong way to look at the problem. What we have been consuming is not gas or oil but degrees of warming from the burning of fossil fuels. When we finally consume all the degrees that humanity can bear, the energy supply has been spent.

We debate incessantly about the new sources required for the energy transition and much less about the underlying human conditions that energy looks to improve. Sustenance, health, comfort. While I can offer little enlightenment about what this sustainable future could be exactly, it does not involve paper straws.

The title of Maçães’ new book foreshadows a less conventional lens of where civilization may be headed: Masters of the Metaverse.